| |

|

|

| |

story

|

“ART

YOU EXPERIENCED?” The

souls of Quik

At first sight, the faces that Quik sprays on to paper,

magazines, maps, and other backgrounds appear to be simple

exercises that are consistently repeated. The faces are cartoon-like

shapes in bright colours, with an expressive look communicated

via the eyes or mouth. Sometimes they appear alone, sometimes

in swarms, a mixture of large and small. Closer inspection,

however, shows countless different expressions: pained or

critical as well as exuberantly cheerful and sweet. It is

not unrealistic to think that these faces depict the moods

of the artist, perhaps in combination with other people and

events. The artist himself refers to these faces as ‘souls’.

These powerful faces, which are applied with relentless energy

to the accompaniment of sixties music - especially by Jimi

Hendrix and Neil Young -, summarize much of Quik’s

oeuvre. In addition to the characteristic graffiti technique,

the most powerful ingredients of his work are the expressive

force of the cartoon-like grimaces that directly confront

the viewer, and the underlying message of the artist about

his own feelings in present-day society. To Quik, present-day

society means New York City, his hometown. Even if he signs

his work in Groningen, he still writes ‘NYC’.

What primarily elevates Quik above many other writers is

the consistency that has characterized his imagery and his

message over a period of more than 25 years.

To graffiti writers, the dissemination of their imago (name,

meaning) is of the utmost importance. Right from the outset,

Quik played a leading role in the generation of train graffiti.

Just as in any other new art movement, graffiti evolved due

to the fact that a few individuals began to change their

style, form, composition, and their use of colour and materials.

During this kind of process, the leading lights come into

contact with other forms of artistic expression, and individual

artists subsequently separate from the mainstream. The great

upsurge of graffiti was primarily based on rivalry between

the writers, eloquently articulated as ‘style wars’:

leaving one’s logo at public locations, spreading a

name, getting known, becoming the best. Compact names and

recognizable (cartoon) figures are logical applications that

could impress other train writers as well as the general

public. The writers began to manifest themselves as true

marketing specialists. Like children of the sixties, they

possess an attitude nurtured by Pop Art, kicking against

the traces and all forms of authority, seeking their 15 minutes

of fame. Their train graffiti pieces are inspired by advertisements

on billboards, transferred and multiplied across various

wagons, set in motion by the train, presented to a million-strong

public every day. After their ‘rebel’ period,

many graffiti artists switch to company-commissioned advertising

for clothes, bags, and the design of toys.

Two aspects played a role in the acceptation of graffiti

as a new art movement in the eighties: first of all, the

interest of the art world itself in commercial art-oriented

trends: the inspiration from children’s imagery, resistance

to tedious and intellectual concepts, entertainment. In addition,

the art world also began to develop an interest in fashion

and advertising photography, in video clips with youth idols,

a kind of regeneration of Pop Art by Warhol and his colleagues.

Graffiti first gained renown via photographs by Henry Chalfant

and Martha Cooper, which were soon collected by museums as

a distinctive form of artistic photography, and subsequently

published in books. Warhol and Cooper were intermediaries,

like art critics and gallery owners, who furnished the public

with large editions of quality items in the ‘super & popular’ spirit

of the times (as Frans Haks, one of the first Dutch museum

directors to take an interest in graffiti, referred to this

style). These intermediaries form the second reason why graffiti

became so popular among museums and private collectors. Early

paintings such as I Am the Smoke King, I Am Black (1982),

Lin! (1982), and Thanx Toddo (1982) were acquired for the

collection of the Groninger Museum via these channels. In

stylistic terms, these early works are quite simple in their

structure: large letters with silhouettes, occasionally evolving

into facial forms as in Thanx Toddo, and a cloudy background,

because graffiti writers are not fond of empty surfaces.

Thanx Toddo!, 1982, acryl spray on canvas, 128 x 298 cm, Groninger

Museum

Lin!, 1982, 143 x 280 cm Groninger Museum

|

|

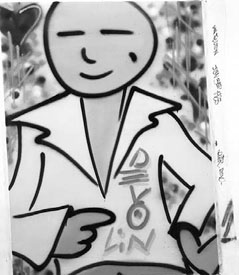

Devo, for my loving mom, 1983, 121 x 91,5

cm Groninger Museum |

One of the greatest private intermediaries

in the Netherlands undoubtedly is Henk Pijnenburg, living

in Deurne. His large collection comprises all the stages

of Quik’s

oeuvre. Several fine examples in this collection show how Quik

transforms the short messages with a cartoon into an image.

Orange Pink Stripes II (1983) merely shows the name QUIK in

orange and pink stripes, highlighted with stars and spirals.

Next, a cartoon face, a heart, a small devil or a doll-like

figure (I’ll never grow old from 1987) start to become

an integral part of the name Quik. The characteristic faces

(souls) pop up in these works as graphic worm-like creatures,

emerging to the foreground in drawings like Dead Souls (1986),

and later becoming the Q of Quik.

Milan Kunc, Mein Haus, 1984, 209 x 240 cm, Groninger Museum

Apart from Pop Art, Quik also became influenced by his meeting

with the Czech /German painter Milan Kunc in the early 1980’s.

Kunc’s work was also acquired and exhibited in the Groninger

Museum in the mid eighties. Kunc’s imagery is multilayered,

stylistically related to Salvador Dali, whose pictures he often

quotes in his so-called Neo-Surrealistic paintings. He depicts

stereotyped worlds, for example the western world as a blue marsh

(the end of the civilization) opposed to the red Eastern world

as the land of the rising sun, with his own studio in a large

skull in the middle. This work from 1984 is entitled My House.

The giant skull resembles Dali with his characteristic moustache.

Almost every small |

|

| |

|

|

image and creature in this painting

is funny and satirical at the same time. Kunc is very concerned

about the decline of the western culture and the violation

of nature. The skullface and the artists palette in the shape

of a face from a 1982- drawing recur in Quik’s souls. |

Milan Kunc, 1982, drawing on paper,

22,8 x 30,4 cm Groninger Museum

|

|

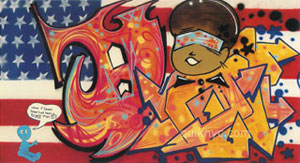

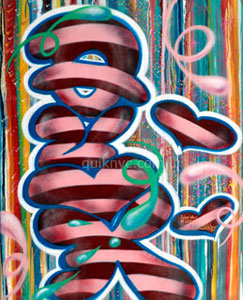

Quik’s work from the

beginning of the nineties displays a baroque, more complicated

style. The letters have become complex compositions in themselves.

The many details in the colours and shapes and the fragmented

surfaces that engender a spatial effect mean that direct legibility

has been sacrificed in favour of a wide range of impressions.

The more abstract a work is, the more it is based on internal

restlessness. An example of this is Wheels

of Confusion, which

dates from 1991 (Groninger Museum).

These baroque works are

a strong outcry of personal emotions. I wish I was blond haired

and blue eyed (1989) in the Pijnenburg collection shows a satirical

self portrait with fragmented hair, eyes, nose and mouth. The

backgrounds, too, are dynamic with many colourful |

expressions

and points. Quik’s development can be clarified by

comparing it to that of his friends Seen (Richard Mirando)

and Blade (Steven Ogburn). Seen and Blade strongly adhere

to the name and the lettering of their original train paintings.

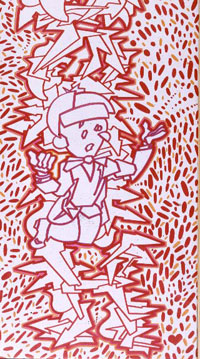

Seen, 1983, 187 x 304 cm, Groninger Museum

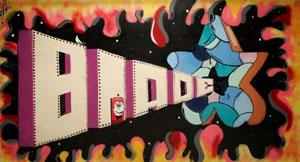

Blade, Come on in, 1983, 179 x 228 cm, Groninger Museum

The letters are occasionally

fragmented or dynamic, like arrowheads against a simple

universe-like background, but they are always robust and

recognizable. Seen is currently oriented toward tattoos – he owns three tattoo shops

in the Bronx and Queens – and also creates reliefs,

three-dimensional graffiti, in which the letter continues

to be the starting point of the image. Although the lettering

also remains an important point of departure for Quik, his

imagery gradually shifted in the course of the nineties toward

a cartoon-like human figure by means of which he attempts

to tell a story. In addition to the faces, this was also

the time in which he began to produce the paintings on the

Playboy centrefolds.

Graffiti never dies!, 1999, 59,7 x 27,8 cm, Groninger Museum

The naked girls often are covered with letters

that are mobile and difficult to decipher, with butterflies

and faces. In this way, Quik improves the ideals of beauty

of the middle-class man. The woman plays a major role in

his themes. Where she has not been painted over or processed,

she appears as a lady with long hair or a beauty queen with

hair stuck up and witprominent breasts, surrounded by glittering

dots. |

|

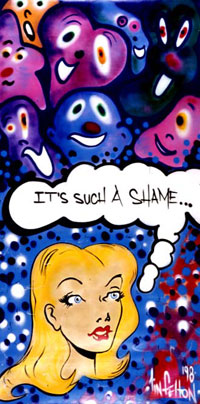

Occasionally Quik will add

a personal remark suggesting that he not only questions the

general American Dream but also his own experience or inner

life. It’s such a shame from 1998 shows how emotional

these remarks can be.

It’s such a shame, 1998, 398,5 x 200 cm, Groninger

Museum

|

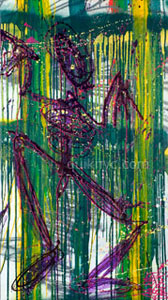

Another theme reinforces

this approach: the emaciated Negro. This figure appears from

1990 onwards. In his studies and drawings, Quik adds more texts

and ideas, thus creating small stories. A party in Pennsylvania

from 1991 (Pijnenburg collection) shows a lynch party. The

negro is hanging from a bare tree, the American flag next to

him. After his divorce, the artist lived in Pennsylvania for

some time and here he discovered to his disgust, strong Ku

Klux Klan-like tendencies among the population. This negro

figure is easily recognized in the poignant painting Killing

Yourself to Live (1993), donated by Quik to the Groninger Museum

at the farewell reception for Frans Haks. The figure attempts

to hang himself, but the quality of the rope is so poor that

the attempt is unsuccessful. The bitter humour is enhanced

by the cheerful background full of joie de vivre.

Killing Yourself to Live, 1993, acryl

spray on canvas, 185 x 156 cm, Groninger Museum, gift from

the artist

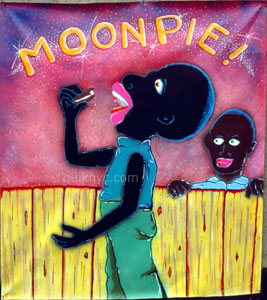

However distinctive it may be, Quik’s cartoon

figure reaches back to the tradition of Sambo, the prototype

of the stupid, inarticulate and lazy ‘nigger boy’,

known in the Netherlands as Sjimmie (in Sjors and Sjimmie)

or Zwarte Piet (Black Pete, St Nicholas’ helper). Although

these figures are often adult, they are treated as children

and also have childish qualities: they are obedient but not

suitable for carrying out difficult jobs. This Sambo stereotype

is used by Afro-American artists such as Michael Ray Charles

from Texas, for example, as a protest against a humiliating

view of the black American. This artist applies the original

Sambo effigy on the billboards in order to convey an extremely

critical message about the ongoing oppression of black people

in the conservative south of the USA – Bush country,

where white people arm themselves to the teeth in fear of

the blacks, encouraged to do so by the weapons industry and

the government. Charles’ paintings are deliberately

primitive and copy the Sambo figure from circus posters,

the game Bamboozled (dealing with double-crossing), and the

tradition of ‘blackface’ (the grease-painted

white actor in films, theatre, and television shows), making

no secret of his unequivocal condemnation. In American society,

the discrimination of the fifties and sixties – the

riots in Montgomery, Alabama (1955, the bus incident with

Rosa Parks), the high school of Little Rock (1957), and eventually

the murder of Martin Luther King (1963) – are still

tangible even today.

|

|

Michael Ray Charles, (Forever

Free) IF I CAN’T YOU CAN’T, mixed media’ on

wood, 114,9 x 92,7 cm. Henk and Leonie Pijnenburg collection. |

On the surface, Quik’s Negro figure does

not resemble Sambo, but it does in terms of content or intention.

Quik’s critical attitude and imagery can be compared

to the work of the New York / Haitian superstar Jean-Michel

Basquiat and to his fellow writer and co-resident of New York

City: Lee Quinones, who has also been active right from the

start. Lee does not portray the position of the black man but

rather that of another oppressed group, the Latinos, in this

case the Puerto Ricans in New York. They constitute a large

community but are underprivileged, as strikingly depicted by

Lee in his masterpiece Society’s Child, dating from 1982.

Lee Quinones, Society’s Child, 1983,

acryl spray on canvas, 360 x 301 cm, Groninger Museum

The victim is a Puerto Rican junkie with his left arm tied

off, giving himself a shot. The clenched fist protrudes forward

in an eye-catching manner. In the background is the shadow

of the Statue of Liberty, as if it were his own shadow. To

him – just like Quik – this is not the American

Dream but rather the sinister shadow side of society. The

figure is a loser, a symbolic yet simultaneously personal

individual to whom the background gives a universal significance.

Lee’s imagery has developed into dramatic pictures

of crime, war scenes, slums, prostitutes, and junkies, from

which the original name and letters have completely disappeared

to be replaced by figurative, strongly realistic representations.

Only the spray technique still enables his canvases to be

classified as graffiti. Quik, in contrast, adheres more firmly

to the origins of graffiti: the word. He sprays short texts

as a direct emotional comment on the depiction of cartoon-like

shapes: real cartoon figures such as Felix the Cat (in: Graffiti

Never Dies!, 1999) (Groninger Museum, gift of Henk and Leonie

Pijnenburg), or his own creations such as the Beauty Queen

and the faces of the black man. His Negro is not fat or silly

and does not display a big captivating white smile like Sambo

does. Quik’s figure is ground down by American society,

which has disappointed him (only taking instead of giving)

and within which he does not wish to live. Nevertheless,

this society has shaped him and will always remain a part

of him. It is a very personal figure that occasionally reacts

in a very direct way to events in the everyday life of the

artist. It is an alter ego that can be coarse and grotesque,

can attempt to commit suicide, or can teach the viewer something,

in much the same way as the artist himself attempts to teach

something positive to children at black schools in New York,

regardless of how difficult the circumstances may be. From

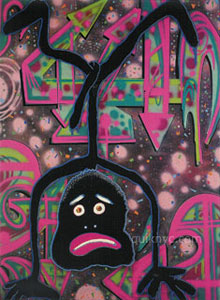

2000 onwards, the Sambo-type has been transformed into a

tortured black man. Sometimes his eyes and lips are bleeding,

and his ribs, legs and arms look like they have been burned

or starved to death. I don’t live today from 2000 in

the Pijnenburg collection has been painted onto an American

flag, literally emphasizing his background. In recent works

from 2004 and 2005, the tormented creature is even stronger

and more desperate, painted in a powerful expressionist style.

It seems that Quik prefers to devote his attention to the

position of the underprivileged rather than to the dissemination

of his own fame (he is sometimes surprised that so many art

connoisseurs value his work so highly). This has also had

a positive influence on his imagery, elevating it far above

the advertising message on the trains. The many faces that

he displays are literally his own faces, and the souls of

all of us.

Steven Kolsteren

Groninger Museum

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cooper

Photo (1982) |

Moonpie

(198x) |

She won’t

love me (198x) |

Crimes

of the heart (1989) |

untitled

(with heart) (1990) |

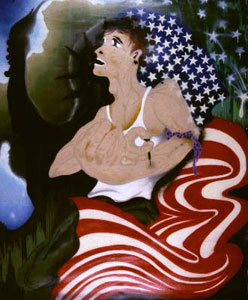

Birth

of a nation (1991) |

What if

Jasper Johns had been a black man (1990) |

Upside

down (1990) |

I don’t

live today (2000) |

Colour

wheels

of love (2001) |

untitled

(2004) |

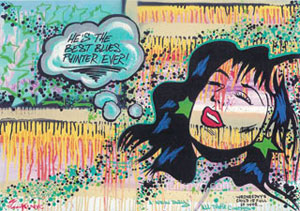

He’s the

best blues painter ever (2004) |

|

|

|